Black, White & Shades of Gray: Leveraging Discovery to Write a Better Brand Story

While product, market, and user research are all now widely recognized as key components of product design, this wasn’t always the case.

For a long time, we thought good ideas automatically made good products, good brands, and good marketing. (Remember Mad Men’s “It’s Toasted” success?)

But taking on product design without doing research is the equivalent of having a conversation without listening. You might make a flawless point, but there is no guarantee it will be relevant to your audience. What does make a good product, much like a good conversation, are good insights, and the ability to learn from them, make sense of them, and deliver a meaningful, relevant interpretation of them. After all, even Don Draper had to ask internal stakeholders about the process before he could come up with his campaign.

“Se non sei curioso, lascia perdere.”

—Achille Castiglioni

(If you are not curious, don’t bother.)

Researching Real Life Behaviors

So let’s make one thing clear: I am most definitely not a scientific researcher or a data scientist. What I am is curious, and that is why I find so much value and pleasure in using qualitative research to discover what makes a good product, a good website, or a good user experience.

But what is qualitative research? The concept is often explained by comparing it to quantitative research, somehow portraying it as its antonym (which it isn’t). In layman’s terms, quantitative research is used to quantify a behavior, event, or result, while qualitative research is used to understand the reasons that led to that behavior in the first place.

While quantitative research provides absolute truths (until proven wrong) and statistically significant results — often in the form of data, percentages, and ratios — qualitative research provides patterns, criteria, and findings. However, these are never black or white in nature. It is the interpretation and the context that make them all the more valuable. And it is my job—through strategic discovery—to make the most of the shades of gray while always finding balance between this sort of discovery and data-driven analyses.

Why We See Value in Qualitative Research

People don’t always behave in quantifiable terms. This is why if I ask you to describe yourself, or even if you took a personality test, your results may vary from one month to the next. Similarly, certain behaviors vary from one session on a website to the next one or based on some seemingly unrelated factor that is extremely relevant to conversions. It is important for us to capture both the results and the context that lead to these, which is why we need to listen, observe, and absorb information.

“Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them.”

—Denzin and Lincoln, The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research

Collecting Findings Through Discovery

User and market research, much like some “fly on the wall” documentaries, require you to simply be there and observe. Other methods can have differing levels of involvement, but the focus is always on the user and their journey. Here are some of the methods you will encounter as a researcher, UX strategist, or product manager.

1. Observational Research and Video Recording

We often use video recording on websites to see how people are navigating our clients’ sites. We observe where people stop, show confusion, click on items that are not buttons (measuring “rage clicks”), and discover some other basic UX challenges.

In product design, when the product isn’t digital, this requires far more creative methods. Observational research might mean you need to go physically follow people as they shop for a product to analyze their moves and interactions. (As an example, I once had to follow cheese buyers around, recording what influenced their decision, how they interacted with the cheese, and what their conditions were both before and after making a purchase.)

This method is one of the most efficient ways to identify challenges without having any personal bias interfere with the respondents’ results. It is a great source of “a-ha” moments in which you perceive things your team would have never guessed, because, well, you aren’t the user. Even if you are, it is likely that you are thinking about these interactions out of their natural context.

P&G used this technique years ago to determine the real reason customers had for using their newly launched product, Febreze. The internal team’s assumption was it could be used in bars to cover the smell of smoke or in homes with pets to alleviate the “pet smell” problem. But by doing some observational research on customers that bought the product regularly, they realized Febreze was not a “pain reliever” (it wasn’t for people who wanted to get rid of the smell), they discovered it was most used as a gain creator, which is often called a “vitamin” in design speak. It was used by customers who completed their house cleaning ritual with a spray of Febreze. This allowed the company to change marketing direction and advertise it directly for this use, causing sales to pick up in the following months. (You can read more about this here.)

2. Interviews

Conducted in person, on video calls, or over the phone, interviews allow for one-on-one human conversations to take place. Here, you can hear the nuances of certain opinions. Obviously, these are not solely observational and the questions you ask greatly impact the answers you may get, which is why it’s good to remember to not ask leading questions. (For example, instead of asking “What is frustrating about this experience?”, prompt the participant with “Tell us about your experience while navigating on this site.”)

It is very important to make the interviewee feel comfortable, which is not always an easy task. If you are just starting in UX research, it will be challenging at first, but it does gets better with a little practice. I am sure, if you are a researcher at heart, you will find a lot of incredible resources about how to conduct a good interview so I will only give you my top three tips:

When possible, do a little digging

This is more relevant when speaking to your client’s team than to users. Consider yourself a journalist for the day. The best way to get good insights is to provide good context for the conversation to take place. When doing an interview with a key stakeholder about their organization, reference their brand messaging. Reference

- an interview that has been done in the past

- a previous message they sent to you

- something that gives you some background on how they think.

Practice active listening

In our lives, we rarely listen without participating, we rarely truly pay attention to a full conversation, and we are unaware of the ways our body language provides cues and alters the way others craft their speech. This is why your first couple in-depth interviews will be exhausting and why you should not be the one taking notes as you interview. So to prepare to be a good interviewer, ask a friend to sit in front of you and tell you a personal story. For 3-5 minutes, look them in the eye, don’t interject, don’t nod, and try not to smile. Just listen.

Let the interviewee tell you what they want to get off their chest

At the end of any interview, before you thank them for their time, tell them you have asked all of the questions you had prepared, and then proceed to ask “Is there anything else I should have asked that I didn’t ask?” Nine out of 10 times, they will continue talking for another 10 minutes about that one thing that has been on their mind and that you would have never guessed.

Also, don’t forget to be yourself. Be human. When starting the interview, before you jump into the difficult questions, smile — even if it’s over the phone, it makes a difference and the tone of your voice will appear friendlier, plus it will trick your brain into enjoying it more.

- Be open,

- don’t overdress,

- learn to master small talk,

- and don’t be too nervous.

They are more scared of you than you are of them!

3. Social Listening

I often say the synonym of the word brand is reputation. In a world where brands have a presence through a variety of channels — some they control and some they don’t — finding what people think of a brand is an interesting and engaging process.

Good research practices require you to consider the perspectives of all users that might provide a variety of insights, and social listening allows you to do so. Start with the controlled channels:

- the client’s store

- website

- social media

- press kit

- brochures.

And hopefully you will read and hear the same messaging statement or variations of it over and over again. The brand should be consistent, although sometimes it isn’t, which is often one of the reasons our clients come to us.

Next, look at channels outside of the company’s control such as comments, reviews, and hashtags. Ask friends who have been in contact with the brand. Look for praise and horror stories, and try to truly make the most of the amount of subjectivity qualitative research allows you to capture.

Discovery is more than collecting requirements for all to ignore. Part of discovery is expanding your knowledge: seeking understanding about the context of the project and interpreting requirements in that light.

—Dan Brown, Practical Design Discovery

Making Sense of the Mess

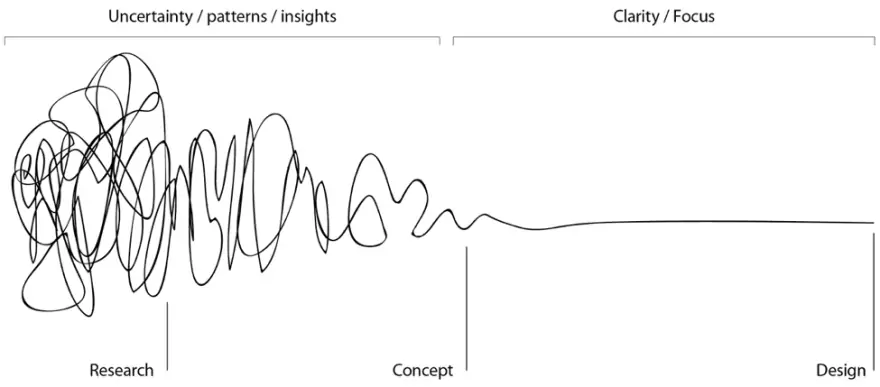

“Design Squiggle” by Damien Newman, Central Office of Design

We get a lot of questions from clients regarding the discovery process, and they often want to know how we know we’ve gathered enough information.

The first rule of discovery is … we do not know until we know.

The second rule of discovery is … ok, you get the point.

Discovery is like organizing your grandma’s attic. You don’t know what you’ll find, you don’t know when you’ll find it, but you know for a fact, there is something valuable to be found.

My former professor and director of strategic innovation at Salesforce, Elizabeth Glenewinkel, always reminded us of the “ABC” of Discovery: Always Be Capturing.

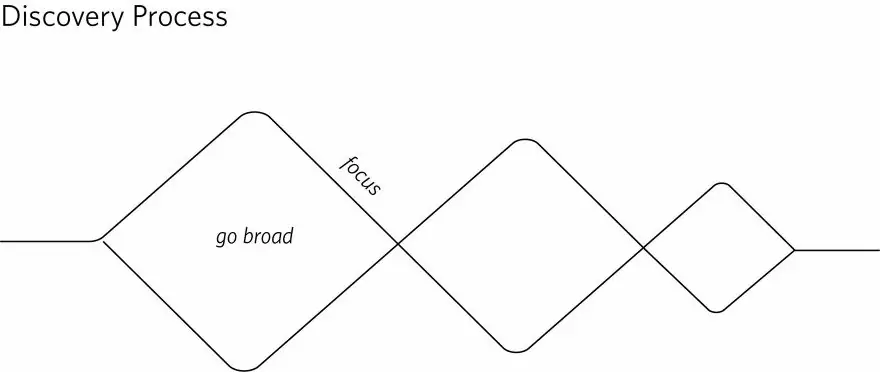

Discovery will require you to think divergently for periods of time, but capturing findings and having deliverables along your timeline will help you converge back and create an actionable roadmap that you, your product design team, and your client (if applicable) agree on.

In order to prepare for discovery, I recommend creating a plan that outlines all of the methods you will use, what questions you expect to answer, what assumptions you have beforehand (to validate or disprove), what findings you uncover, and how they impact the project. Each one of these items should be a field in a master discovery matrix.

Aim for each insight you gather to:

a) Answer the questions you originally outlined

b) Provide you with more questions and have an impact on your discovery plan that should be tracked

c) Validate or disprove an assumption

d) Sometimes lead to an a-ha! moment that will impact your product design

If you are lucky, you will get a lot of a-ha! moments through your research. Make sure to not only capture them, but transform them into visual and tangible models for you or your design team to follow.

We like to use variations of what in UX is called user story to capture behaviors. Here’s an example:

As a ___ (user), I need ___ (product/feature) to ____ (function) so that I can ____ (experience).

We do this because processing research is hard, and the objective of the strategist and researcher is to make the complex become simple. This is why some other research methods require more visual templates, such as

- journey maps,

- persona templates,

- vision canvasses,

- design criteria boards,

- affinity clustering,

- and more.

The second thing you should know about discovery is what Dan Brown outlines in his book, Practical Design Discovery.

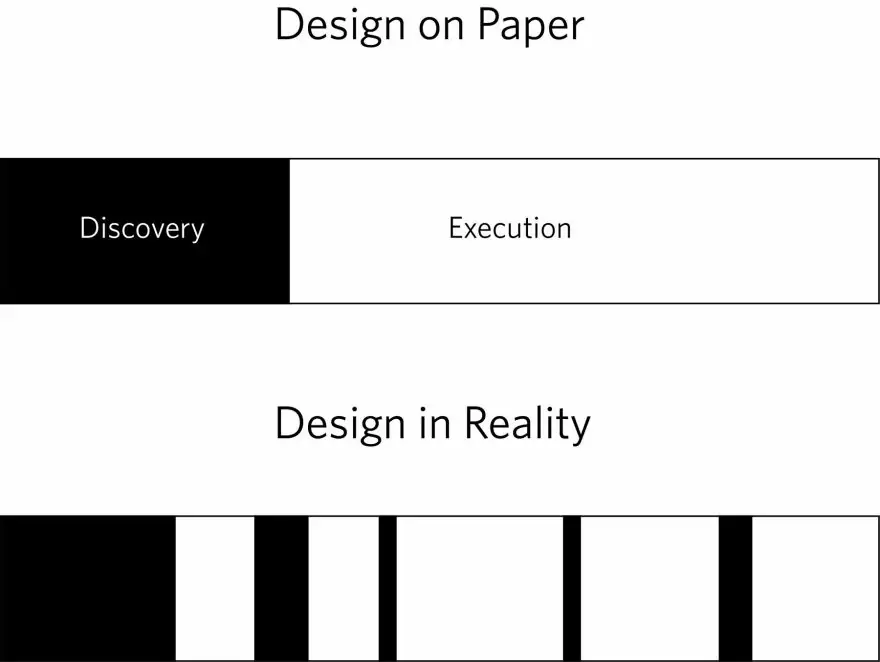

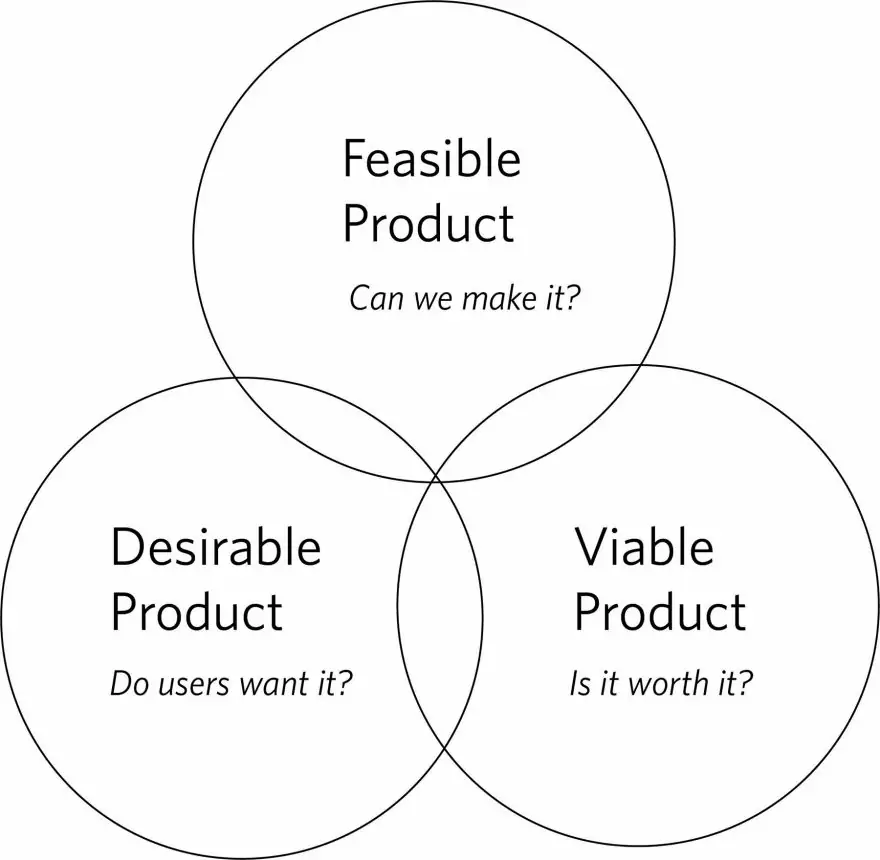

Discovery will continue throughout the process, which is why we always prefer to be the ones doing discovery, strategy, design, and development. This vertical integration allows us to truly inform our experts along the way as we continue to understand how the insights gathered at the beginning of the discovery process truly affect the client, the organization, how solutions are adopted, and what design needs to accommodate for. Remember, the focus is always on finding that perfect balance between desirability, feasibility, and viability.

That’s All, Folks!

You may have noticed a recurring pattern throughout this article in the form of film and TV references that help explain my thinking. What does that tell you? Maybe that I started my career hoping to tell stories as a filmmaker. What I loved the most about writing scripts is that you needed to work on character development and that I learned to ask myself the question “What would I do if I were not me?” on a daily basis, which turns out to be extremely helpful now as a researcher and strategist.

But mostly it’s a reminder that strategists, researchers, and UX designers are all storytellers. We develop a world in which it makes sense for characters to have the journey they believe in. And, as it turns out, characters in films are not half as interesting as those you will meet in research, which always makes this process exhilarating.